The mayor of Venice recently announced that the city would spend a full year commemorating one of the most notable personages in its history, the man who embarked on a world-changing journey linking Europe and East Asia.

This year’s Carnival of Venice, wrapping up on Tuesday, was centered on the theme “To the Orient: Marco Polo’s Amazing Journey,” marking seven centuries since his death. It celebrated his legendary travels, discoveries, and encounters with non-European cultures.

Mayor Luigi Brugnaro said the carnival was “an opportunity to plunge into the tale of the young Venetian Marco Polo, which unfolds somewhere between reality and fantasy to create a fascinating narrative that continues to captivate us and make us dream.”

Marco Polo died on January 8, 1324, just shy of turning 70. The anniversary has promoted scholars, artists, economists, and adventurers to visit this fascinating, controversial person. Many questions remain about specific details of his life, involving who he was, where he was born, how he traveled, whom he met, and where he went.

Marco Polo was likely born to a merchant family in Venice. A few years ago, during a visit to the Croatian island of Korcula, I met a local judge named Vladimir de Polo. He and his wife explained over the course of the entire afternoon that there was no question that Marco Polo was born on the tiny island, however. The de Polos even pointed out the house where the famous traveler was supposedly born. Venetians claim a different house.

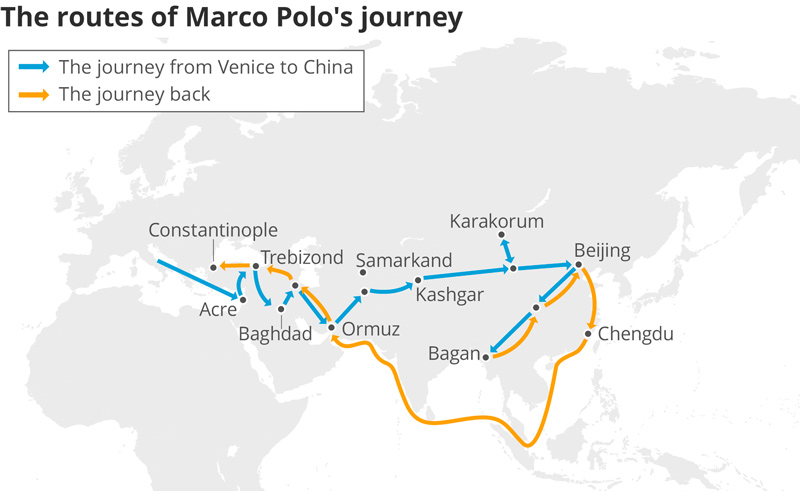

When he was 17, Polo joined his father and uncle on their second journey to Asia. They sailed from Venice to Acre, visited the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem, and continued onward to China. For 20 years, between 1271 and 1291, Polo remained in East Asia. He was sent on diplomatic missions for Mongol Emperor Kublai Khan, traveling throughout the empire.

Shortly after his return to Venice, Marco Polo, then 40, was captured by the Genoan navy, which was at war with the Venetian navy. In prison, he met Rustichello da Pisa, a writer who convinced him to write about his adventures. The resulting book was titled “Il Milione” (“The Travels of Marco Polo” in its English translation), which has been a global bestseller ever since.

‘There was always trade between East and West, but it was indirect – someone went from one place to another and handed over the goods, and then someone else transported them onward. Marco Polo personally made the whole trip from Europe to China.’

“The Travels of Marco Polo” has never been translated into Hebrew. Rereading R. E. Latham’s English translation makes it clear that while Polo did travel through a world full of pirates, wild animals, and dangerous storms, he was more interested in the organized trade routes and administration of the Mongol Empire. The writing is that of an accountant who was also an adventurer with a tendency toward preoccupation with baubles. He liked nothing more than describing trade worthy goods like precious stones, spices, and silk.

Recounting his visit to Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), he wrote, “they have also the most precious thing to be found anywhere in the world; for in this island, and nowhere else in the world, are produced superb and authentic rubies. The island also produces sapphires, topazes, amethysts, garnets, and many other precious stones. And I assure you that the king of this province possesses the finest ruby that exists in all the world…”

Prof. Michal Biran, head of the Institute of Asian and African Studies at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and director of a research project on the Mongol Empire, dismisses those skeptical about Marco Polo’s travels. She says there is no real doubt about his historical existence or his traveling to China. The source of the skepticism, Biran says, is a book published in 1995 by Francis Wood, a historian and then curator of the Chinese collection at the British Museum.

‘Marco Polo shows us China from their perspective. It’s possible that he slightly exaggerated his proximity to Kublai Khan, but contemporary scholars do not question the veracity of his travels.’

Wood’s book, “Did Marco Polo Go to China?” claims that the traveler never went beyond the Middle East and that his descriptions of China were based on hearsay from others. Her arguments lean on details that didn’t actually appear in his book. For example, Wood notes that much of the Great Wall of China had not been built at the time Marco Polo was writing, but he never actually wrote about the wall. Wood argues that the names Polo gave to what he saw were based on Persian, therefore concluding that he received assistance from Muslim travelers. But Persian was the lingua franca throughout the East in that period.

“Marco Polo was in China and mostly traveled with the Mongols. Hence his importance,” says Biran. “He shows us China from their perspective. It’s possible that he slightly exaggerated his proximity to Kublai Khan, but contemporary scholars do not question the veracity of his travels.”

What did Marco Polo do in China for 17 years?

“He describes things related to administration and financial matters. Those things interested him. We believe that he was an official who managed trade related to the salt monopoly. That is a subject closely tied to the [Mongol] dynasty. It seems that he was a minor official, but he knew enough to describe the kingdom.

Why is the book important?

“Until Marco Polo, Europeans’ world terminated just beyond the Middle East. During the Mongol period, Europeans began to reach the Orient, and their world expanded dramatically. Polo gave [the West] the most comprehensive description of China, India, and Asia in general. It suddenly emerged that the world was surrounded by indescribable wealth. The book’s importance is seen in the fact that when Columbus set sail 200 years later, he took Marco Polo’s book with him.”

Was this a good period for the Mongol Empire?

“Kublai Khan was a grandson of Genghis Khan and one of the empire’s greatest leaders. It was the peak of the Mongol dynasty’s opulence and glory in China and this dynasty’s last conquest. They conquered south China, the world’s most populous and wealthiest region, which had never been conquered.

“It was the first time that that a single political entity controlled the land and sea routes in a vast part of Asia. At the time, China was the center of the world. It’s already been said that for Europe to rule the world, it had to know that there was a world – and we owe that to the Mongols.”

How did trade along the Silk Road change?

“There was always trade between East and West, but it was indirect – someone went from one place to another and handed over the goods, and then someone else transported them onward. Marco Polo personally made the whole trip from Europe to China. The world became more open, and people more mobile.”

Between Acre and Jerusalem

To get a sense of the Israeli part of Marco Polo’s journey, I traveled from Acre to Jerusalem. It didn’t quite replicate his original journey, as I traveled by train, shrinking the travel time between the port and the holy city to two and a half hours. But visiting the two cities allows an understanding of what the great traveler saw 750 years ago.

When Polo’s father and uncle visited Kublai Khan on their first journey to Asia, the emperor gave them a letter for the pope requesting that he send oil from the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem and 100 Christian missionaries who could teach about Europeans’ way of life. On their journey back from China, they arrived in Acre, the capital of the Crusader state of the Kingdom of Jerusalem. They encountered an unexpected problem.

The pope had died in 1268, and no successor had yet been elected. The brothers waited in Acre for two years. Finally, after consulting with an Italian cardinal in the city during the Eighth Crusade, they decided to return to Venice in the meantime. When they went back to Acre a year later, with Marco in tow, there was still no new pope. They waited for a while longer before visiting the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem, obtaining oil as a gift for Kublai Khan, and heading east.

They sailed from Acre to Turkey, where they received welcome news. Their cardinal friend had been elected pope, taking the name Gregory X. The three Polos returned to Acre and got a letter from the pope to Kublai Khan. They were joined on their journey by two priests, who abandoned the difficult trek shortly afterward.

In Acre and Jerusalem, you can see remnants of the time of Marco Polo’s visit. In both places, you can see and appreciate the power the Crusaders held in the area. Acre and Jerusalem were Christian bastions at the presumed ends of the earth. They were built to impress, and they remain impressive to this day.

To follow in Marco Polo’s footsteps, you have to start in the Knights’ Halls in Acre. This fascinating site, extensively renovated in recent years, was completely empty on the day of my visit. Rain, war, and the dearth of tourists meant that I walked alone through the vast halls and between the stone arches and the courtyards.

This was a fortress belonging to the Knights Hospitaller military order, which operated in Acre until the city fell to the Mamluks in 1291, 20 years after the Polos’ visit. The order was a religious and military organization that assumed the defense of the Kingdom of Jerusalem. At the time, the city was populated by the Crusader nobility, residents of the Italian communes in the area, traders, sailors, and religious pilgrims. The Venetian Polo family felt at home in Acre. Their circumstances were quite comfortable, and commercial opportunities seemed limitless.

My train ride from Acre to Tel Aviv took about 90 minutes, followed by another hour to Jerusalem. Marco Polo took several weeks to travel between the two cities by foot. He rode on horseback, meandering and stopping wherever possible.

From the Old City’s Jaffa Gate, I descended the almost completely silent market to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. The scene was similar to what Marco Polo would have seen. In 1270, Jerusalem was in the midst of an economic depression. A decade after the Mamluks had defeated the invading Mongols near Ein Harod. Baybars, the Mamluk sultan of Egypt, attacked the cities that remained in European hands, reducing Christians’ power to just three cities: Acre, Tyre, and Sidon.

Christian sites in Jerusalem were almost totally destroyed; the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, which Marco Polo visited, was one of the few undamaged ones. The church, located in the Old City’s Christian Quarter, is where, according to most Christian traditions, Jesus was crucified, buried, and resurrected. It was originally built in the 4th century, but when Marco Polo visited, it was under the control of the strictly Islamic Mamluk Kingdom. The kingdom greatly feared another crusade from Europe.

Today, the Church of the Holy Sepulchre is undergoing massive renovations and looks like a construction site. It is dimly lit by wax candles and electric bulbs. Nevertheless, the building retains a grandeur and majesty. You can see why Venetians like Polo saw in it a familiar place, a European signpost – perhaps the last – on the road east. Polo spent three years traveling eastward before he met the khan. After three hours, I returned home and drank tea that had come from the Silk Road.

Art on the Silk Road

Marcello Bolognari is a historian who recently completed his Ph.D. on Marco Polo at the Ca’ Foscari University of Venice. He says he researched Venetian archives for years and found three previously unknown original documents related to Polo’s grand journey. The revelations included the existence of a daughter about whom historians were unaware. Until then, it was believed that Polo had three daughters – but Bolognari found out about another daughter, Anaisa, born out of wedlock, who lived in Venice and died five years before her father.

Bolognari spoke with me this week as a representative of the MarcoPolo700 Foundation, an initiative by different groups based in cities along the historical Silk Road, from Venice to Beijing. Bolognari represents the Venetian group, which is dealing with historical research. The foundation’s projects mainly target high school and university students. The project it’s currently focusing on centers on art in 10 Silk Road cities.

“We consider Marco Polo the most important traveler in human history,” says Bolognari. “The objective of marking the 700th anniversary of his death is showing the world what we know because of him. He was a complex and courageous man. In my opinion, he is a very Italian figure. He could reach the highest levels of humanity, but also the lowest. For example, look at his conflict with his family over property when he returned to Venice. He is a dramatic figure.”

Fifty years ago, Italo Calvino’s fantastic book “Invisible Cities” was published in Italy. The novel depicts conversations between Kublai Khan and Marco Polo, with Polo reporting events in the crumbling empire to the emperor.

In one scene, Polo “describes a bridge, stone by stone. ‘But which is the stone that supports the bridge?’ Kublai Khan asks. ‘The bridge is not supported by one stone or another,’ Marco answers, ‘but by the line of the arch that they form.’ Kublai Khan remains silent, reflecting. Then he adds: ‘Why do you speak to me of the stones? It is only the arch that matters to me.’ Polo answers: ‘Without stones, there is no arch.'”