Crack open your average history textbook, and you’ll probably find the tragic tale of the Justinianic plague, a pandemic that tore across ancient Europe and Asia between 541 and 750 A.D., claiming an estimated 25 million to 50 million lives.

The plague—a bacterial disease ferried from rodents to people via infected fleas—is widely believed to have culled the era’s Mediterranean populations by up to 60 percent. Historians have argued that its scourge altered the course of history, ushering in the demise of the eastern Roman Empire, the rise of Islam, and, ultimately, the emergence of modern Europe.

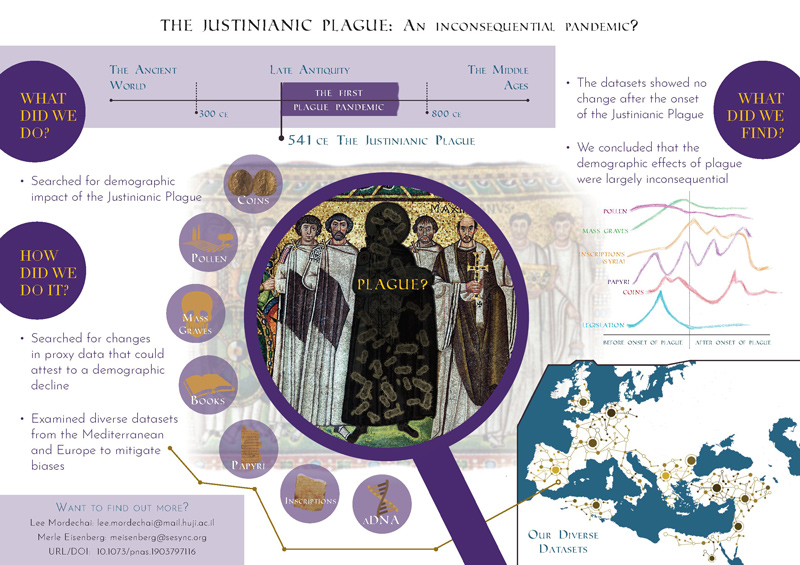

Now, new research is challenging this age-old narrative. After poring through data ranging from historical texts to pollen samples and mortuary archaeology, an international team of researchers has concluded that reports of the havoc wreaked by the Justinianic plague may have been exaggerated. The not-so-devastating disease, they contend in a paper published this week in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, didn’t actually claim that many lives—and was a far cry from the empire-toppling, society-reshaping debacle it’s often made out to be.

“It’s easy to assume infectious diseases in the past would have catastrophic results,” lead author Lee Mordechai, an environmental historian at Hebrew University of Jerusalem, tells CNN’s Katie Hunt. “Yet, we used every type of data set we could get our hands on found no evidence in any of these data sets to suggest such a destructive outcome.”

Some key facts remain unchallenged. The Justinianic plague—named for Justinian I, the eastern Roman emperor in power during the first outbreak—arose in the sixth century, intermittently recurring throughout Europe and the Middle East until around 750 A.D. While accounts of the plague’s severity varied, some modern historians gleaned its cataclysmic effects from a subset of particularly sensational ancient texts, reports Ruth Schuster for Haaretz.

But when Mordechai and his colleagues scoured a wide range of data, they found little evidence that the Justinianic plague had left a massive blemish on human history. Compared with the more widely known Black Death, another plague caused by the same bacterium that (more definitively) killed tens of millions in Europe during the Middle Ages, the earlier pandemic was fairly tame.

Ancient pollen data from the time of the first epidemic suggests the plague’s appearance had little impact on land use and cereal cultivation—proxies for population size and stability. Archaeological finds also show that coin circulation and currency values remained stable throughout the outbreak. And group burials, constituting five or more individuals in the same grave, didn’t seem to experience an unusual boom during this plague-ravaged period.

The Black Death, on the other hand, “killed vast numbers of people and did change how people disposed of corpses,” study co-author Janet Kay, a Late Antiquity scholar at Princeton University, says in a statement.

A thorough search of the written record revealed that texts from the time were conspicuously lacking in references to plague or severe declines in socioeconomic wellbeing.

Bacterial DNA isolated from human remains confirms people died from the disease, the authors conclude—but not to the extent of population collapse or political pandemonium.

“The idea that it was a blanket catastrophe affecting all parts of the Mediterranean, Middle East and central and western European worlds needs to be rethought,” Princeton University’s John Haldon, a historian of ancient Europe and the Mediterranean who was not involved in the study, tells Bruce Bower at Science News.

The researchers’ findings leave the drivers of social changes straddling Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages murkier than ever before. Historians may never pinpoint a singular cause for the eastern Roman Empire’s fall. But if they do, Haaretz’s Schuster reports, Mordechai is fairly certain it was “apparently not the plague.”