In the 1990s, leading Israeli scholar Yosef Garfinkel, head of the Institute of Archaeology at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, led several seasons of excavations at the Neolithic site of Sha’ar Hagolan in northern Israel. Among other things, the researchers uncovered several clay figurines depicting the deity Mother goddess presenting unnaturally elongated heads. For their artistic qualities, the figurines were exhibited in the most important museums around the world. For Garfinkel, they represented the spark which prompted him to investigate a new field of research, the history of human dance.

“While I was trying to understand more about their specific shape, I came across other figurines with elongated heads, dancing figurines,” he explained to The Jerusalem Post.

From that initial trigger, Garfinkel would eventually author a book and most recently a paper which reformulates the way of looking at this form of art.

“Most of the existing academic work about the history of dance focuses on the past 400 years in Europe, with some research done also on ancient Greek, Egypt and Mesopotamia. However, my view is that it is necessary to dramatically expand the horizon, potentially going back to even half a million years ago,” he added.

The archaeologist has suggested that the evolution of dance can be divided into five different phases, presenting increasing sophistication.

In the first phase, dating back to earlier than 100,000 years ago, dancing was an individual activity associated with courtship and mating.

“Animals such as insects and birds dance to win over their partners, ancient humans were doing the same,” Garfinkel pointed out.

Items uncovered in burials in the Carmel mountains – the oldest ever discovered, dating back to about 100,000 years ago – offer a glimpse in the second phase: dance in rite of passages. Materials such as red ochre and imported seashells which were unearthed in the site were often used in those occasions.

“Rites of passages, such as birth and death but also the ceremonies which celebrated the coming of age of children, represented an important element in the life of those communities, a way to highlight the individual’s social status as well as to keep records in societies where there were no newspapers or anything of that kind,” Garfinkel told the Post. “Dances, which had evolved into a communal activity, accompanied those rites.”

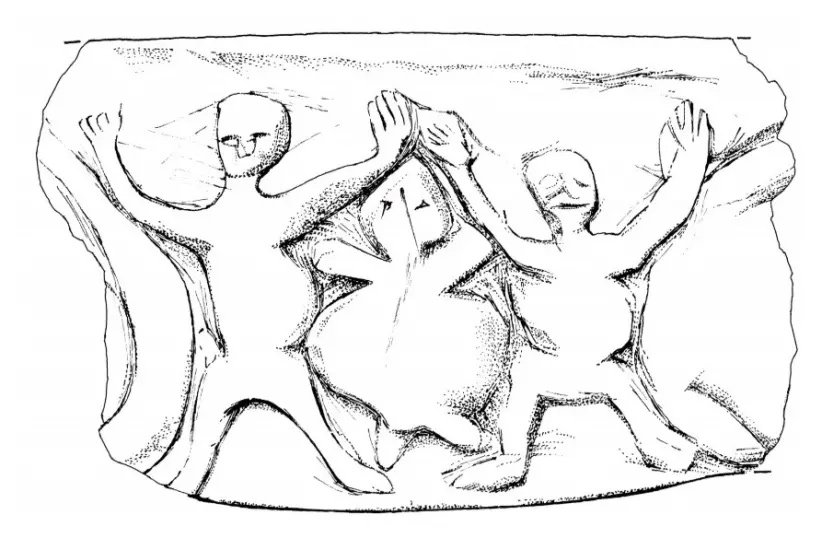

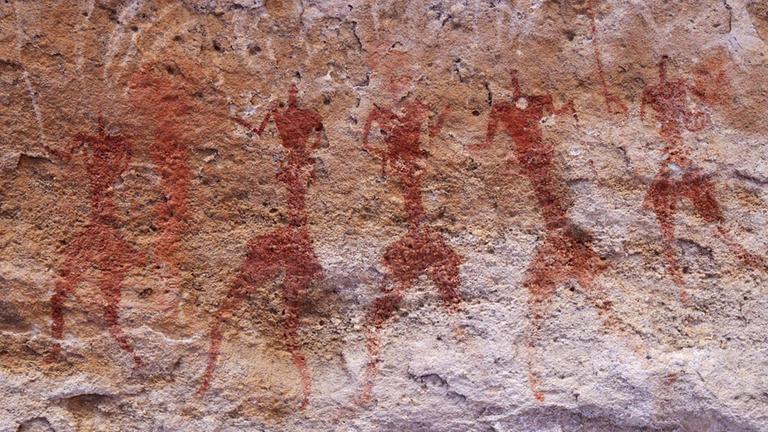

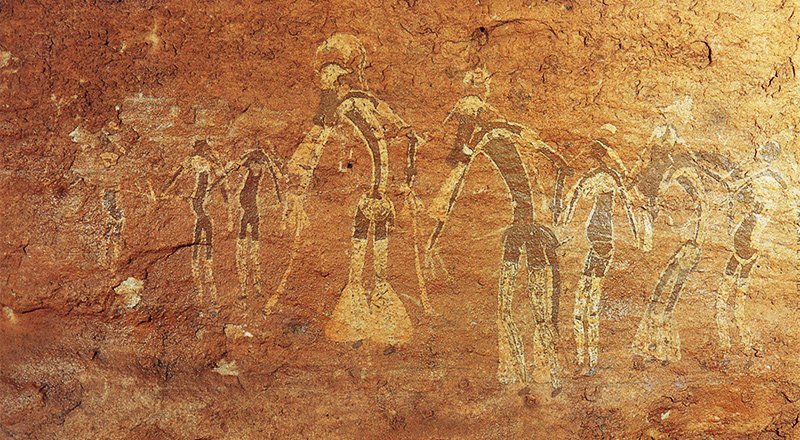

About 40,000 years ago, dance became more intrinsically connected with the supernatural, marking the beginning of a new phase, during which selected individuals, such as shamans, would perform specific rituals for a specific purpose, for example healing the sick.

Garfinkel described this phase as the one of “dance and trance.” Many examples of figurines and images depicting human figures in plastic positions dating back to this period witness the phenomenon of dancing, while others presenting fantastic features, often mixing human and animal traits might suggest a state of hallucination, he pointed out. He also highlighted how trance plays an important role also in more modern religious traditions, mentioning among the others mystic movements in Islam and Judaism.

Jewish tradition embodies well the following phase, beginning around 10,000 years ago with the development of agricultural societies: dancing during calendrical rituals, with entire villages participating in ceremonies organized not for specific occasions as in the past, but at set times of the year to celebrate moments connected to the farming cycle.

“If we look at many Jewish holidays, they fall at the beginning of different agricultural seasons,” Garfinkel pointed out.

Indeed, many Jewish texts, from the Bible on, include references to dancing.

“Rabbi Shimon ben Gamliel said: ‘There were no days of joy in Israel greater than the fifteenth of Av and Yom Kippur. On these days the daughters of Jerusalem would go out in borrowed white garments in order not to shame any one who had none. All these garments required immersion. The daughters of Jerusalem come out and dance in the vineyards,’” reads a passage in Mishna Taanit.

The academic pointed out that the frequency of references to dancing in Jewish tradition represents a sharp contrast with what happened later on in Christianity.

“In the Bible, dancing is mentioned dozens of time, in the whole New Testament only once,” he said, adding that this has been a factor in how dance was viewed in the Western culture for a long time and possibly also into why so much of its evolution has not been the focus of more academic attention.

According to Garfinkel, the fifth phase developed together with more complex urban societies in the Near East around 5,000 years ago. When individuals started to develop specific expertises also dancers became professionals, as attested by wall paintings uncovered in Egypt dating back to the 3rd millennium BCE.

The scholar emphasized that the different phases did not cancel but rather accumulated on each other, as it can still be seen in the different forms of dancing; individual and communal, erotic and ritual, amateur and professional, that exist and attract people to this day.