Editor’s note: Prof. Nissim Otmazgin is the Director of the Institute for Asian and African Studies at Hebrew University, and Associate Director of the Harry Truman Research Institute for the Advancement of Peace. His PhD dissertation, which examines the export of Japan’s popular culture to Asia, won the Iue Asia Pacific Research Prize in 2007.

The Japanese Embassy in Tel Aviv saw some unexpectedly clad visitors last week. Its lecture about “Kawaii” and how it is used in the Land of the Rising Sun’s diplomacy attracted cosplayers dressed like their favorite Japanese animation (anime) shows, alongside Japanese language students.

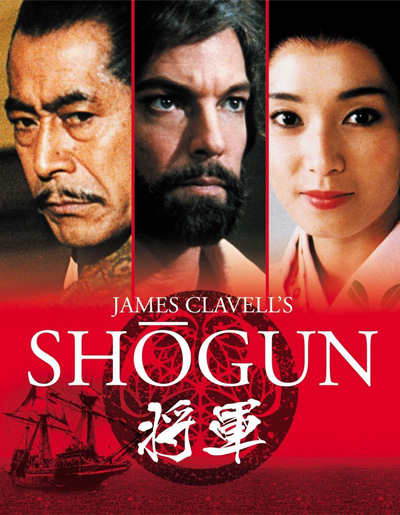

Speaking was Hebrew University Prof. Nissim Otmazgin, who began by sharing with the audience how as a child he watched the 1980s miniseries Shogun, an adaptation of the 1975 novel by James Clavell, and decided that when he would grow up he would visit Japan, become a samurai and marry a Japanese woman. “I got two out of three,” he jokes, “not so bad all things considered.”

Shogun was, as he pointed out, one of the first cultural products that presented a positive image of Nippon after films such as the 1957 The Bridge on the River Kwai presented the cruelty and harshness suffered by British and American soldiers held captive by Imperial Japanese forces. Clavell, himself a prisoner of war, wrote the 1962 novel King Rat based on his experiences.

Shogun was, as he pointed out, one of the first cultural products that presented a positive image of Nippon after films such as the 1957 The Bridge on the River Kwai presented the cruelty and harshness suffered by British and American soldiers held captive by Imperial Japanese forces. Clavell, himself a prisoner of war, wrote the 1962 novel King Rat based on his experiences.

Japan has a long history of being fascinating to the West. Japanese high-art, such as the prints of Hokusai, are credited for inspiring Edgar Degas and Claude Monet. In 1992 Shifra Horn published A Japanese Experience based on her five-year stay in Japan. While the book was severally criticized by some, it was also one of the earliest books in Hebrew meant for a wider audience about modern Japan. Jewish-American writers such as Joel Rosenberg described a fictional world in which the Jewish people and the Japanese merge in his 1989 Not for Glory science fiction work, and Jake Adelstein, the first non-Japanese to be hired as a reporter for the Yomiuri Shinbun Tokyo daily, released Tokyo Vice in 2009, a book dealing with Japanese crime.

Otmazgin points out that, among the Israeli press, Japan is usually covered in a positive way when compared to China, for example. One reason for the warmth Israelis show Japanese culture, he argues, is manga comics and anime, the staple elements of the “otaku” culture (Japanese slang for “geek”, which has since become used in the West as a title for geeks with a particular affinity for manga, anime and Japanese video games). “They come for the manga,” he half-jokes when speaking about his students, “and we teach them Japanese language and culture.”

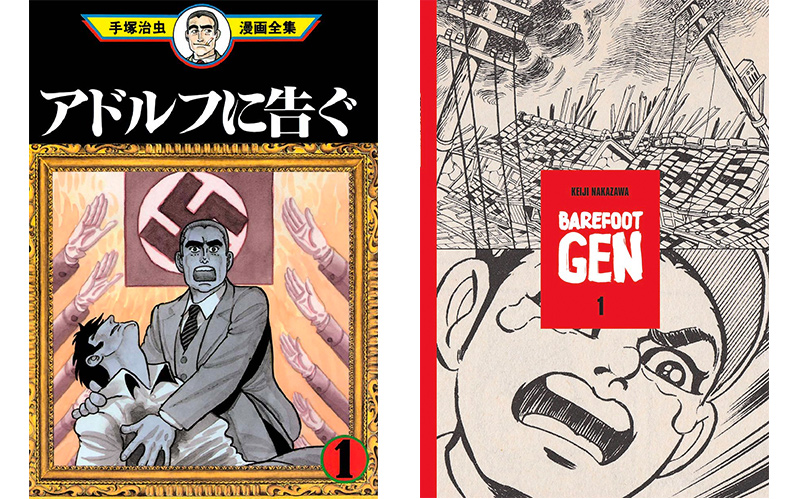

In fact, Israelis enjoy manga so much, the Hebrew University recently opened a whole library of manga where students can read the 1983 work by Osamu Tezuka Adolf and the 1973 work by Keiji Nakazawa Barefoot Gen. The first is about, what else? Adolf Hitler and two other characters with the same given name, one Jewish and the other Japanese. The second is about surviving Hiroshima and based on the author’s own experiences. Both works focus on a message that became very powerful in post-war Japan: War is a terrible thing.

According to Otmazgin, Israelis enjoy Japanese culture so much that Tel Aviv is the third city in the world in the number of sushi eateries per capita after Tokyo and New York, and there are so many Israelis willing to explore Japanese pop culture the Convention of Anime and Manga in Israel recently held its 10th annual convention here. In fact, Japan makes more money selling anime to the US than it does on selling it coal and steel. So how did pop culture become so important to the Japanese state? A top official Otmazgin spoke with openly admitted he doesn’t care for either comics or animation and, if it was up to him, he would promote high-brow Japanese culture such as tea-ceremonies and shamisen music. “But such events only attract a few hundred people,” he shrugged, “and when we do an event about anime the hall is packed, so we do what works.”

Of course, not everyone in Japan shares this view, and there are many who recognize the power and potency of this more common aspect of Japanese culture. An example of this is Deputy Prime Minister and Finance Minister Taro Aso, who previously served as both foreign minister and prime minister. Aso is a known otaku, and once said that per week, he read around 10-20 manga magazines (unlike in the West, where individual comic titles are put out by themselves in their own magazines, manga publishers in Japan put out massive magazines with several new issues of series compiled together, which often clock in at 400-500 pages). In fact, according to a BBC report, Aso’s well-known love of manga actually caused manga stocks to jump, some as high as 71%, when he became the leading candidate for prime minister after Shinzo Abe’s resignation in 2007. Notably, Aso believes that manga can be used as a bridge to the world.

Japanese officials sort of stumbled on their unusual cultural wealth as Japan confronts several difficult situations. The first is the economic slump. While still one of the wealthiest nations, Japan is no longer expanding as it once did. Predictions that Japanese wealth will subdue the West never actually quite happened. Japan is also losing one million people every three years due to low birthrates. This led the Japanese government to ease restrictions on immigration and explore various options at attracting skilled workers, from offering Japanese-Brazilians to return to the homeland to seeking to offer more student visas than ever before.

In addition, cases such as the 1995 Tokyo subway sarin attack and the 2011 Fukushima nuclear disaster left many Japanese people wondering what their society is going through. If post-war Japan was promised to be a technological marvel that won’t fail, or a safe society in which violence will be eradicated, both things did not quite happen.

Faced with these difficult themes, pop culture opened up a path to Japanese young women to extend their period of adolescence by the fashion of Kawaii. The word means “cute” and it is a collection of fashion and cultural statements: It’s cute to put cat ears on one’s head; it’s cute to carry one’s books to school in a backpack shaped like an animal. It is interesting to note that during the Shogun period (1185-1868) the term was employed to shape a new understanding of women. Once regarded as animalistic, women began to be seen as “cute.” This might have coincided with the prolonging of youth culture in the West, meaning that if in the West young people were encouraged to put off marriage and the duties of adulthood, in Japan the adaptation of Kawaii culture might be seen by some women as a reprieve from assuming the duties of motherhood and marriage.

Kawaii diplomacy then is the discovery by Japanese officials that their country is rather liked in East Asia and across the world for producing things like fictional video-games characters Mario, Donkey Kong and Link from the Legend of Zelda, all created by Shigeru Miyamoto, and animated films like Princess Mononoke, Howl’s Moving Castle and the Oscar-winning Spirited Away, both by Hayao Miyazaki. While sales of electronic devices on which to play video games or watch shows generate profits, who will buy such things unless they have excellent games to play and movies to watch?

This led to some surprising decisions by noted Japanese officials. Prime Minister Abe dressed up as Super Mario when he appeared in the closing ceremony of the Rio Olympic games, a nod to the character invented by Miyamoto meant to signal to those watching, “Come visit Japan, you already like us.” Doraemon, a fictional manga character created by Fujiko Fujio, was named an ambassador of Japan. Likewise, Hello Kitty, created by Yuko Shimizu, was named special envoy to China. Starting from 2009 young women have been selected, and trained, to serve as Kawaii ambassadors around the world. This is an official position currently held by, among others, Misako Aoki, president of the Japan Lolita Association.

All of this is reflective of a sense of pride in Japanese culture overall and its growing popularity across the world, something referred to domestically and abroad as “Cool Japan.” This phenomenon has skyrocketed with governmental support, and has expanded to both entrepreneurial and academic spheres across the world. In addition, this isn’t limited exclusively to Japan, with both Taiwan and South Korea having utilized similar methods to popularize their culture around the world. Indeed, there are some who believe that the growing interest in and popularity of South Korean culture today could potentially overtake that of Japanese culture.

Israel is no exception to the spread of “Cool Japan.” The Association for Anime and Manga in Israel (AMAI) every year holds two large geek conventions, CAMI and Harucon, which center heavily on otaku culture. For the past several years, these conventions have been held with the support of the Japanese Embassy, which not only helps with the budget, but also provides lecturers. According to Japanese Press and Cultural Attaché to Israel Shion Kawai, the use of otaku culture such as these conventions is a great way to spread and promote Japanese culture, and therefore Japan as a whole. It is for this reason that at these conventions, they also have desks handing out flyers in English and Hebrew covering everything from travel brochures and tourist guides, to academic scholarship applications and booklets about Chiune Sugihara, the Japanese vice consul to Lithuania during World War II who helped nearly 6,000 Jews escape during the Holocaust.

And of course, Japan is only set to become an even bigger destination for Israelis soon.

“In 2018, over 40,000 Israelis traveled to Japan,” Kawai told In Jerusalem earlier this year. “There are charter flights operated by Sun d’Or, El Al’s subsidiary.” He added that with the addition of El Al’s direct flights to Tokyo – slated to begin in March – these numbers will increase even more.

The use of Kawaii diplomacy was actually adopted by Israel toward Japan. In 2014, the Israeli Embassy in Tokyo released a seven-episode anime series called Israel, Like!, which attempted to market the Jewish state to Japanese tourists and increase interest in its culture. The series focused on two sisters, Saki and Noriko, who come to Israel on vacation, and each episode focuses on a particular site in the country while discussing various interesting facts about Israel, such as its role as the Start-Up Nation and the popularity of Max Brenner. Throughout this journey, the mascot of the Israeli Embassy, Shalom-chan, often chimes in with other interesting facts.

According to then-ambassador to Japan Ruth Kahanoff, the series aimed to “connect to Japanese pop culture and use anime to reach the Japanese audience, especially youth, and display the Israel beyond the conflict.” And according to an embassy spokesperson, “The feedback we’re getting for the project is unprecedented. The show is receiving massive media attention all across Japan. The main goal is to showcase the lighter and original aspects of Israeli society all the while paying homage and respect to Japanese popular culture.”

While cynics might argue that soft power, including Kawaii diplomacy, is something nations turn to when they’re at a loss as to what other answers they might offer, others might point out that anime and manga are essential ways through which Japanese society had worked out, and is working out, through the trauma of committing brutal acts during the Second World War, being bombed with nuclear weapons and losing a world war. In modern anime, such as the 2006 series Black Lagoon, based on the 2002 manga by Rei Hiroe, characters are ethnically different and the protagonist of the series is a young Japanese man who feels that the traditional values of hard work and immersing oneself in the needs of the firm are hollow and lacking. This concept of internationalism, or globalism, is known in Japanese as Kokusaika and had been introduced to a variety of educational programs.

In Israel, both Tokyo Trial, a miniseries focusing on the trials conducted in Japan of high officials accused of committing war crimes and crimes against humanity after the collapse of the imperial dream, and Black Lagoon are now available for viewing. Offering those interested two very different opportunities to explore just how much vitality and change are possible in a society once totally devoted to conquest.