The physicist Prof Hanoch Gutfreund has a passion and excitement for the project we are discussing that certainly can’t be explained by rules and theories. Albert Einstein was unique, he tells me in a Zoom conversation from Jerusalem this week: possibly the greatest scientist who has ever lived, but someone who tackled all human problems – of morality, and of political dilemmas – with the same interest and energy he brought to physics.

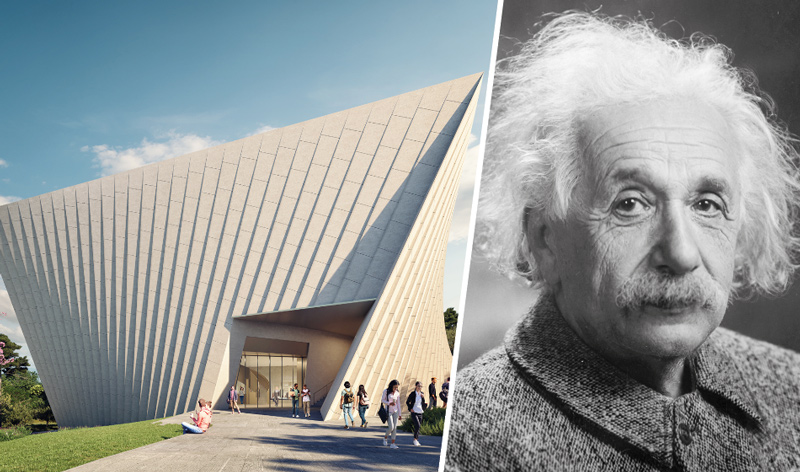

Gutfreund’s fascination with Einstein, whose work he has taught to hundreds of students at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, where he has a chair in theoretical physics and is a former president, has extra force just now. Construction work has begun on Einstein House, a stunning building on the Hebrew University’s Safra Campus at Givat Ram. Designed by the world-renowned architect Daniel Libeskind, it will contain the full Einstein Archive. As curator of the archive, which the physicist and co-founder of the Hebrew University left to the institution on his death in New Jersey in 1955, Gutfreund says he has decided to devote the rest of his own life to promoting Einstein.

Another unique aspect of the Nobel laureate is his enduring appeal: nearly 60 years after his death the fascination is only growing. In 2008, a historian of science wrote an article complaining that too many books are written about Einstein and suggesting a moratorium until all the material in the archives is explored, Gutfreund says. “It had no effect. Since 2008, there have been more than 85 new books on Einstein,” and, with a smile and a silent davka, “Four of them are mine.”

For someone interested in politics and morality, Einstein certainly had plenty of material to work with. He lived through two world wars, the disintegration of empires and the quest of the Jewish people to establish a homeland. He wrote about it all and his letters form part of the archive, which extends to more than 80,000 items. “He corresponded with politicians, with philosophers with thinkers with members of the Zionist movement, so there is a lot.” But there is also Einstein’s personal library, which is very much that of a young Jewish intellectual in Berlin in the 1920s and contains not a single book of physics.

“Scientists in those days were well-read,” Gutfreund says, Einstein no less than his contemporaries. “The canon of western philosophy is mightily represented there, [as are] literature, history and Judaica.”

At the heart of the archive is Einstein’s masterpiece, his 46-page manuscript of the general theory of relativity, which he wrote in 1915, and which introduced the famous E=mc². “Everything that we know today about the universe, about the Big Bang, black holes, all these household names, gravitational waves, everything that we know today follows from that from that manuscript,” Gutfreund says. “So it’s mind-boggling. It’s so exciting, once you grasp it.”

Libeskind, the New York-based architect of the Jewish Museum Berlin among other notable buildings, has designed a building for the archive in the form of a twisted cube. Its complex geometry is influenced by the physicist’s drawings, which flowed from his insights into the nature of the universe: its curve is the curve of spacetime.

A cornerstone for the three-storey building, which will extend to 29,000 square ft and will include a reconstruction of Einstein’s office, was laid in June.

The project has received generous support from the philanthropist and art collector Jose Mugrabi, along with funding from the Israeli government.

Libeskind had always had an interest in Einstein. “[He] is not something that just landed on my desk,” says the architect, whose son Noam studied at the Hebrew University and is now an astrophysicist. “I have been thinking about the implications of his thoughts on the world ever since I recognised the name.” Libeskind’s aim was to create something that touched on all the aspects of Einstein’s genius, he said, including his political belief in Zionism, adding: “Translating scientific breakthroughs and knowledge to the level of everyday perspectives, that’s the challenge.”

Libeskind, a child prodigy on the accordion in his native Poland, when asked whether Einstein the violinist is included in the design replied that the building itself was a kind of musical composition as it does not have a front, a back and a side. “It’s conceived as a continuum. And the continuum is ever-shifting and ever-changing.” The acoustics in the building will also show that the building is based on the mystery of geometry itself, he adds, and he hopes visitors will have “a musical sense to their experience of the spaces”.

The building is not – that soulless of words – a ‘centre’, or even a museum. Einstein House will be a home for the archive in every sense, a purpose-built residence that will welcome visitors. Once the building is complete, the hope is that it will welcome schoolchildren, university students and the public, including, once Israel’s conflict with Hamas is over, some of the thousands of tourists who will visit Jerusalem once again.