Editor’s note: Recently, Hebrew U researchers recreated ancient beer from 5,000 year old yeast. The cousin of the Hebrew U lead researcher managed to get a couple of yeast samples from that project and ended up making bread with mixed results! Click here to read the original beer story.

A sour, unfamiliar, and not particularly pleasant smell began to waft through the house, not what you would expect from bread that was fresh out of the oven. But this wasn’t ordinary bread, it had risen thanks to some exceptional yeast that had been through a long and arduous journey before arriving in my home. We sliced it, ate it, and survived to describe the taste of bread made from 5,000-year-old yeast.

Yeasts are single-celled fungi that are found more or less everywhere. The baking yeast that can be purchased in supermarkets is a version that has been improved throughout history, but along the way there have been many other types of yeasts, some of which returned to life in an unusual study that was published last month.

In the study, researchers from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Tel Aviv University, Bar-Ilan University and the Israel Antiquities Authority, managed to make beer from yeast cells that had survived in clay vessels that had stored beer thousands of years ago. To prove that these weren’t just wild yeasts that can be found anywhere, the researchers sampled dozens of other vessels that weren’t used to store beer, along with the ground and rock at the archeological sites. Only in one clay lamp was any yeast found, and this was unusable for beer making. Moreover, yeasts similar to the ones found are used in traditional African breweries.

According to the researchers, the beer they produced from the yeast found in the Philistine city of Gath, today known as Tell es-Safi, was pretty good. The beer made from Egyptian yeast found at Ein Habesor was less successful.

Ronen Hazan, a microbiologist from the Institute of Dental Sciences at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, who headed the beer study, is my cousin, which is how I was able to obtain two tiny samples of ancient yeast, which survived in clay pots at Ein Habesor and which date back more than 5,000 years.

It should be clarified that these are not yeasts that have actually survived 5,000 years, but the descendants of yeasts that were fermenting beer in the time of the Pharaohs. They are the survivors of a yeast colony that was preserved for thousands of years thanks to a little nourishment and moisture from the earth. It’s reasonable to assume that they’ve changed somewhat over the generations, but the characteristics of ancient beer yeast were preserved in their DNA, and these yeasts are markedly different from the modern ones that you buy in the supermarket and apparently also from the wild yeasts that are used by boutique bakeries to grow their cultures.

But these were beer yeasts. What, you may ask, do they have to do with bread? That’s actually an anachronistic question. The ancient baker didn’t know the exact composition of what was making his bread rise, nor did his friend, the brewer, known what was fermenting his beer. One could assume that the same single-celled fungi were being used by bakers and brewers, so these yeasts might also have been used to bake bread 5,000 years ago.

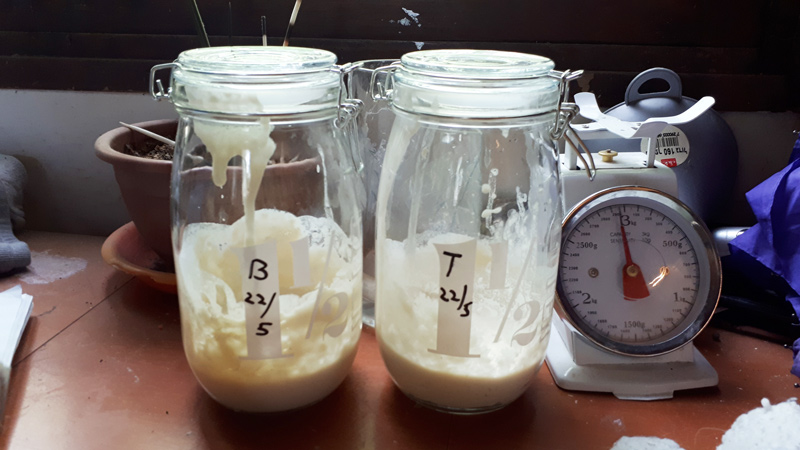

Our experiment was not scientific, however interesting. I took the two test tubes home and began growing cultures. I have some experience with cultures and I thought it would take a few weeks to grow the yeasts to have enough for baking by gradually feeding them small quantities of flour and water.

But after 5,000 years of being stuck in the pores of clay jars buried in the ground, these yeasts were eager to get moving. It was like raising a school of piranhas; within two days they had devoured a cup of flour and were asking for more (yeasts ask to eat when the culture gets acidic and bubbles more vigorously). The fact that I received concentrated yeast grown in a lab probably didn’t hurt.

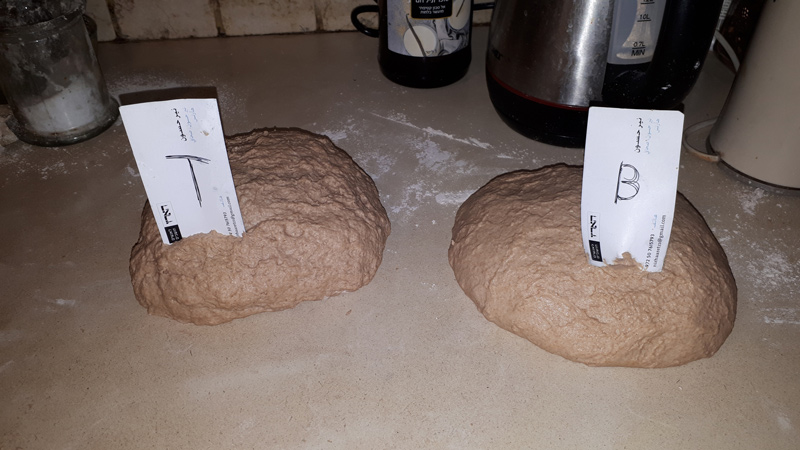

Within a few days I had a large quantity of effervescent cultures ready for baking. The first loaf was made with whole spelt flour and the second with white flour, in an attempt to determine how the yeast contributed to the taste of the bread. As expected, the dough rose very quickly. The baking, as noted, was accompanied by a strange smell, somewhat like goat cheese, or a damp cave, or an unfamiliar alcoholic drink. It’s hard to describe a smell.

And the taste? Here we had a disagreement. Hazan and others who tasted it claimed it wasn’t bad. But it was hard for me to free myself of that heavy smell so I think – how to put this delicately – that wasn’t very tasty. In other words, if the price of exiting Egypt was that we had to eat matza instead of this bread, then maybe that wasn’t too high a price to pay.