March 23, 2023 – A group of natural history museums, organized by the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History in Washington DC, the American Museum of Natural History Museum in New York City, and the Natural History Museum in London, has mapped the total collections from 73 of the world’s largest natural history museums in 28 countries. This is the first step of an ambitious effort to inventory global holdings that can help scientists and decision-makers find solutions to urgent, wide-ranging issues such as climate change, food insecurity, human health, pandemic preparedness, and wildlife conservation.

Beyond the walls of their public galleries, the world’s natural history museums serve as the guardians of an unprecedented archive of the history of our planet and solar system. These natural history collections provide a unique window into the planet’s past, and they are increasingly being used to make actionable forecasts to chart our future. Museums have traditionally acted as independent organizations, but this new approach imagines a global collection composed of all the collections of all the world’s museums.

To better understand this immense, untapped resource, lead scientists from a dozen large natural history museums created an innovative but simple framework to rapidly evaluate the size and composition of natural history museum collections globally. The findings were published today in Science magazine in the paper, “A Global Approach for Natural History Museum Collections.”

Gila Kahila, from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, participated in the project.

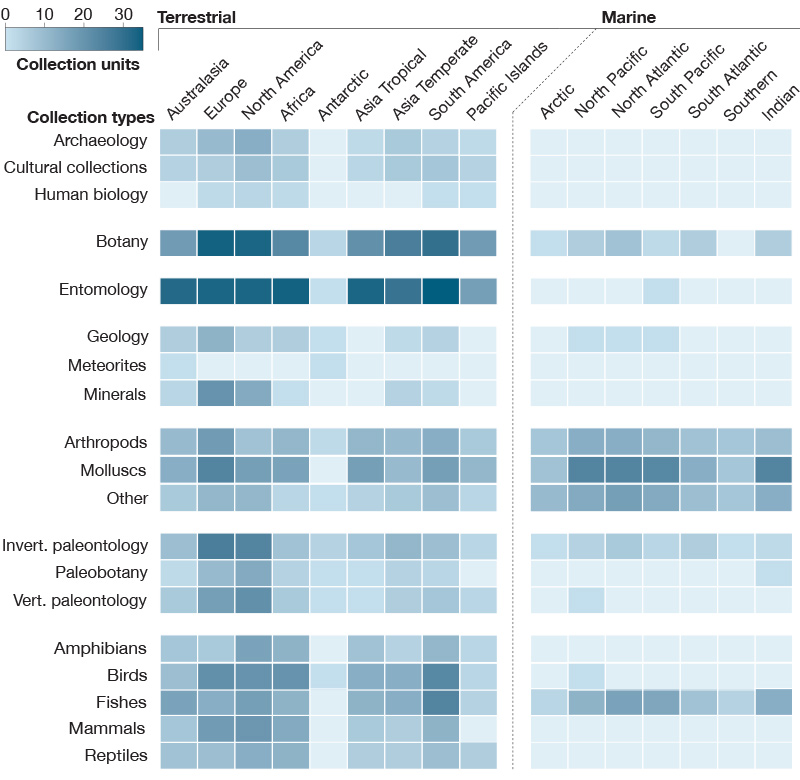

The survey organizers created a methodology that could rapidly survey collection holdings across museums by creating a common vocabulary of 19 collection types spanning the entirety of biological, geological, paleontological, and anthropological collections and 16 terrestrial and marine regions that cover the entirety of the Earth.

“We wanted to find a fast way to estimate the size and composition of the global collection so that we could begin to build a collective strategy for the future,” said lead author Kirk Johnson, Sant Director of the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History. Johnson co-led the effort along with Ian F. P. Owens (formerly at the Natural History Museum in London and now the Executive Director of the Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology) in collaboration with more than 150 museum directors and scientists representing 73 natural history museums and herbaria.

The survey confirmed an aggregate collection of more than 1.1 billion objects, managed by more than 4,500 science staff and nearly 4,000 volunteers. While the aggregate collection is vast, the survey showed that there are conspicuous gaps across museum collections in areas including tropic and polar regions, marine systems, and undiscovered arthropod and microbial diversity. These gaps could provide a roadmap for coordinated collecting efforts going forward.

The report is a significant summary, but it is only the first step in surveying the global collection and tapping its enormous potential. Natural history collections are uniquely positioned to inform responses to today’s interlocking crises, but due to a lack of funding and coordination, the information embedded in museum collections remains largely inaccessible. With strategic coordination, a global collection has the potential to guide decisions that will shape the future of humanity and biodiversity.

By creating this framework and survey, project organizers aim to create a foundation for the global museum network to work together to support future global sustainability, biodiversity, and climate frameworks using knowledge gained from museum collections. This will enable all museums to be more strategic as they plan their collection efforts in the future.

The authors also recognize that the historic concentration of large museums in North America and Europe can be a barrier to knowledge-sharing and perpetuates power imbalances rooted in the colonial history of museum science. In the future, it is crucial that the global collection also reflect and support museums elsewhere in the world.

“Natural history collections are the evidence from which scientists derive knowledge, including knowledge that can be applied to critical issues facing our planet today,” said Michael Novacek, curator in the Division of Paleontology and former provost of science at the American Museum of Natural History. “This has never been more urgent than today, as global biodiversity loss and climate change are accelerating.”

“This global view of natural science collections emphasizes their combined potential to help us act in response to the planetary crisis. It also demonstrates an ongoing commitment and responsibility to build equitable international collaboration and capacity with partners from all countries, harnessing the latest technological advances to further scientific understanding and make data available for all. This vast and progressively united infrastructure of collections and expertise represents a crucial resource in scientific understanding and prediction of global change, supporting action to avoid disaster,” said Doug Gurr, Director of the Natural History Museum in London.

The paper considers applications of collection-based research, focusing on case studies that explore how museum natural history collections can be used to study pandemic preparedness, global change, biodiversity, invasive species, colonial heritage, and museomics (study of DNA from museum specimens). Case study examples of each of the above applications are available here: https://bit.ly/3Ts2ZSm

As the authors write, “The long-term security and value of natural history collections depend on developing global and local partnerships that demonstrate not only their relevance for specific scientific, societal, and conservation challenges but also for the benefits that apply to every person on the planet.”

The full Global Collections dashboard is available here: https://rebrand.ly/global-collections

The full list of participating institutions and authors can be found here: https://bit.ly/3Ts2ZSm

Locations of participating natural history museums

These 73 museums collectively hold more than 1.1 billion objects:

Heatmap of global collection units

Any collection object in any museum can be categorized into only one of the 304 cells (19 collection types by 16 geographic regions). A “collection unit” is a single museum’s holdings within a single cell. For 73 museums, there are 22,192 possible collection units. The heatmap shows the 1957 collection units with more than 10,000 objects.