RAMAT BEIT SHEMESH, Israel — Located in the middle of nowhere, a massive 6th-century church was an unexpected find when four years ago archaeologists performed routine tests in Ramat Beit Shemesh prior to the construction of an ultra-Orthodox neighborhood.

But while the church itself came as a surprise, its intriguing mosaic dedication to a “glorious martyr” is even more of a mystery. Just who was he — or, perhaps, she?

Delving into the intrigue, The Times of Israel toured the impressively large church compound, its companion exhibit in the Bible Lands Museum, and went down a rabbit hole on the internet. After consultation with an ancient Greek expert, the Hebrew University’s Dr. Leah di Segni, we now know that according to the inscription’s grammar, it could have been a female.

Di Segni even offered up one candidate, the Holy First Martyr Thecla the Equal to the Apostles, whose feast day was celebrated earlier this month.

The Times of Israel visited the glorious martyr church just after an October rain storm. Despite the early signs of autumn, the hot sun still beat down on our heads, drying the mud from the site, which is 1.5 dunam or just over a third of an acre in size.

Plagued by reporters, Israel Antiquities Authority excavation head Benjamin Storchan was eager to show off the unique architecture and mosaics — and just as keen to prepare it for winter and protect the precious floorings by covering them with white sand bags.

The church was initially erected circa 543 CE under the reign of Emperor Justinian in the 6th century CE (527-565). The church compound was in use until about the early 9th century and sprawls in many directions. It includes a side chapel with a large carved stone baptismal font, and a rare intact subterranean crypt.

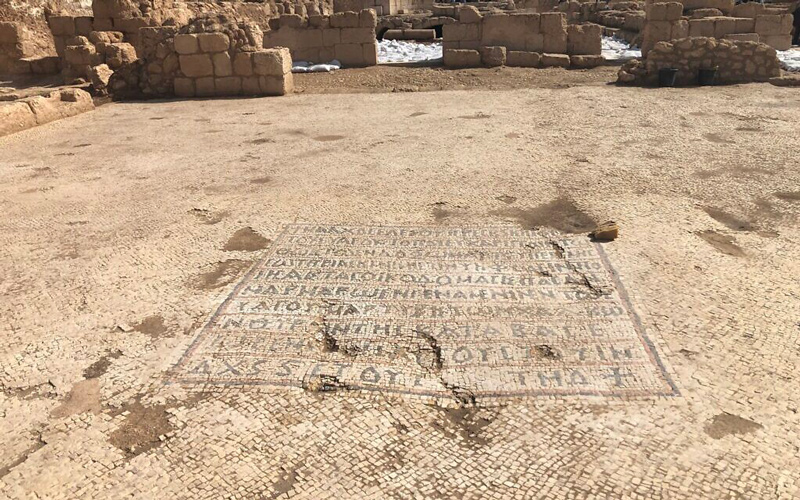

The church’s flooring is decorated with polychromatic mosaics depicting fruit, flora and fauna, and geometric designs. By far the most impressive image is a detailed imperial eagle, which, alongside an inscription recording the donation of Emperor Tiberius II Constantine (574-582 CE), ties the site to the widespread Byzantine empire, according to Storchan. But while the design may have been dictated from afar, the execution of the mosaic was a local job.

A chapel, where the eagle is found, was added under Emperor Tiberius II Constantine. The chapel, said Storchan, allowed the church priests to perform the eucharist twice daily, which he said gives an indication of just how many pilgrims visited this out-of-the-way church that he said must have subsisted on a tourist economy for the 300 years it was in use.

Storchan, a thirtysomething, bushy-bearded Orthodox Jew, laughingly calls the site “the little Hagia Sophia of Beit Shemesh,” tying this church with a network of other imperial edifices. “It was the same money source,” he said. “In terms of what it means, it’s the same ballpark.”

The church and the crypt are filled with circular patterns, said Storchan, which symbolize death and rebirth. Like the crypt, site where baptisms were performed in the quatrefoil (four-leaved) crucifix baptismal font — impressively carved from a large single block of stone similar to that of King Herod’s bath from his palace in Jericho — is also reached by two entrances. The font, today in a secondary position at the site, is large enough for adult immersion — a personal rebirth, he said.

In the spacious front courtyard before the entrance to the church, a large, 10-lined Greek inscription is impossible to miss. It is here that Storchan found the reference to the glorious martyr.

They didn’t teach this in Hebrew school

Storchan, who immigrated to Israel at age 18 from Detroit, Michigan, is learning on the job about early Christendom.

“History is history,” said Storchan when asked how it is that a practicing Jew is now deep in the midst of the Byzantine Empire. “As an immigrant, I see it as part of the heritage we receive,” he said, and another piece of the puzzle that is the Holy Land.

There are several puzzles involved with the church. Why, for one thing, was it packed up, locked up and abandoned? “The doors were sealed in hopes of return,” he said.

But the biggest mystery is assuredly the identity of the glorious martyr. Storchan said he has read night and day about Byzantine-era pilgrims and their diaries to try to figure out who this glorious martyr could be. The mystery, he said, increases his desire to continue his research.

Who this glorious martyr is has not yet been deciphered, but not for want of trying. Ever the feminist, I asked Storchan at the excavation site whether there was anything in the grammar of the inscription to decide whether the presumed “he” could actually be a “she.” The archaeologist laughed and said he too had asked epigrapher di Segni the same question.

Contacted via email by The Times of Israel, di Segni wrote, “The glorious martyr could indeed be a female, at least grammatically speaking: both the adjective and the noun are unisex (same form for man and woman).”

Di Segni was quick to point out, however, that “statistically a male martyr is much more likely, for many more male martyrs are mentioned in the sources, some of whom have churches dedicated to them.” She said that of the martyrs known in this region, those who were more likely to be labeled “glorious” include Theodorus, George, Sergius and Stephanus the protomartyr.

“But there is also at least one famous female martyr, Thecla, who has a church dedicated to her at Kfar Kama, and a cult also in Byzantine Jerusalem,” wrote di Segni.

It turns out that there are several churches dedicated to Thecla in the borders of the modern Jewish state, including one in the Holy Sepulchre and one on the Mount of Olives in Jerusalem. Around the globe, there are many, many more Thecla churches, the most famous being a cave-tomb in southern Turkey’s Seleucia. To my layman’s eyes, the online images of this tomb are rather similar to the crypt in Beit Shemesh.

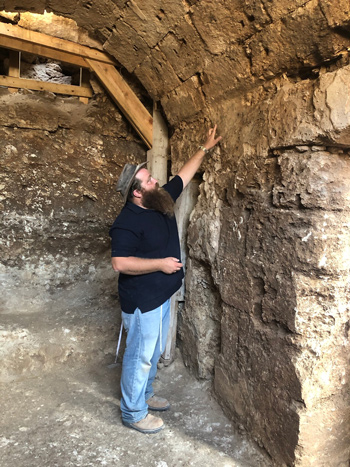

Into the crypt

One of the 5,000 youth volunteers that helped excavate the site initially discovered the existence of the subterranean crypt, said Storchan. He had found a hole in the flooring and a rock was dropped down. According to how long it took to hit bottom, Storchan knew they’d discovered something vast.

The team inserted cameras through the hole and they saw an archway, indicating a vaulted roof, and a large hollow space. When they got inside, they found the crypt was filled shoulder-high with earth.

It was a space that no one had used for well over 1,000 years. The most recent archaeological remains discovered inside were 300 hand-sized 9th-century clay lamps, likely left by pilgrims who would have used them as prayer intentions and as eulogia, souvenirs from their Holy Land journey, said Storchan.

The crypt’s entrance is bookended by two staircases and there is a window with an eastern facing facade at its far end. Found just above where the reliquary would have stood, the window was paned with green-blue glass. The site has offered up the largest collection of such glass in the Holy Land, some of which is on display at the Jerusalem Bible Lands Museum’s “Glorious Martyr” temporary exhibit.

“You think of a crypt as a dark, mysterious place. Why a window?” wondered Storchan under the now boarded-up portal.

The entire domed room was encased with imported marble panels. On the structure’s stone blocks, there are square holes where the marble was anchored. The mix of the glossy white marble walls with green-blue light conjures up images of water. Filled with flickering oil lamps, it would have been a memorable sight, to be sure.

Storchan said that his team has consulted with experts to conduct virtual 3-D reenactments of how the sun’s rays would have traveled through the window, and what would have been emphasized in their path. But, alas, there is no Indiana Jones-esque moment of finding the Ark of the Covenant. Nothing of known import — not even the reliquary niche — would have been illuminated, he said.

In addition to its luxurious marble finish, there were bronze gates to the crypt, said Storchan. The glorious martyr was gated from the public with a chancel screen, and only a very small piece of the box’s lid was discovered. It too is now on display in the Bible Lands Museum.

The crypt itself lays directly under the church’s own chancel, which separated the main church hall from the area devoted to the clergy, such as the eucharist table. The fine, open lattice work of the reassembled chancel screens can be seen at the museum exhibit and are unique in their interlacing circular patterns.

As Storchan speaks, the acoustics of the underground room are notable. He recounts how monks and nuns from the neighboring Beit Jamal monastery have visited several times to pray for the archaeologists and sing — in Hebrew — in the domed space.

“I’m doing my passion, they’re doing their passion, and they’re intertwined. It may sound strange, but they strengthen us in a spiritual way… They’re a third party supporting me in a different way than I’m used to,” he said.

Who was St. Thecla

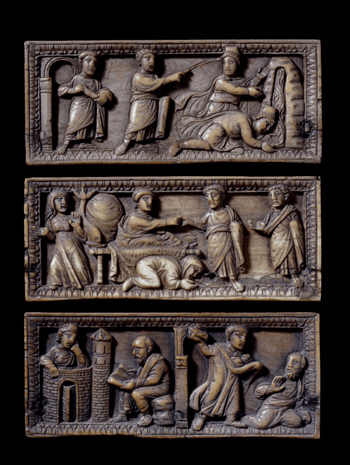

Born to wealthy parents, Thecla was a do-it-herself Christian, who converted after hearing sermons by Paul from her window in the city of Iconium, in today’s Turkey. Her story is recounted in several formats, including the late second century The Acts of Paul and Thecla and the 5th-century Acts of Thecla.

Roughly, after her conversion to Christianity, Thecla’s fiancé objects to her new-found celibacy and she is persecuted in several forums and cities. She fights wild beasts and is saved by a she-lion, she baptizes herself by jumping into a vat of seals, she dresses as a man and escapes certain rape, is swallowed up by a large rock when rapists/sorcerers again come for her when she’s in her 90s.

In most accounts, she baptizes new converts, she’s a healer and a preacher — although some versions that prefer to circumscribe female roles in the church leave her clergy-like activities out. But in all cases, she’s one feisty virgin and an early inspiration to many women, from Eugenia of Rome (who died in 258 CE), until today.

Thecla was very widely venerated in the 5th-6th centuries throughout the Byzantine empire, including in the Holy Land, and holds two titles in the Orthodox rite. She is called “Equal-to-the-Apostles”, which according to Orthodox Wiki is “one whose work greatly built up the Church,” and “Protomartyr: the first martyr in a given region.” She is honored for having “devoted her life to God at a time when all Christians were shunned,” according to the website.

What are the chances that she is the church’s glorious martyr?

“I have never studied statistics,” wrote di Segni, “but I believe that on the one hand, with four ‘likely male martyrs’ against just one female, the latter would have a 20% chance of being the glorious martyr of Ramat Bet Shemesh. On the other hand, the sample (the total number of cases of martyrs described as ‘glorious’ in our region) being so small, I’d say that, like when you toss a coin, the chances of a female martyr are 50-50.”

However, archaeologist Storchan isn’t optimistic that we’ll ever really know who the glorious martyr was. He said he doesn’t truly expect to find an identifier onsite.

“The pilgrims knew where they were going,” he said with a shrug. “They didn’t need a ‘Welcome to Disney World’ sign.”