In the summer of 1944, 14-year-old Kalman Perk and his family were taken from the ghetto in Kovno, Lithuania, to the train station, where they were packed into a cattle car. “Everyone knew it was headed to the death camps,” he later related. In the car was a small opening, covered in barbed wire. One of the passengers tore away the wire until his hands bled. He then tried to force his way out, but he was too big to fit through it.

Perk’s family decided to take the opportunity to throw the boy out the window and try to save his life. “My son, you have always been mischievous and independent and you know how to get by. Don’t forget to wear your cap, with it you look like a real shegetz,” he recalled his mother telling him. Other relatives begged the boy to jump, so that at least one family member would remain alive. “You’ll tell the story of our family, that way it will be easier for us to die,” they said.

Crying, he replied that he didn’t want to be a young orphan and would rather die with them. Nevertheless, “I answered immediately that if I survived I could tell the world what the Germans did to the Jews of the Kovno ghetto,” Perk wrote in his autobiography, “Shetihyeh Ben Adam: Darki Mehashoah Le’olam Hamada” (“Be a Mensch: My Journey from the Holocaust to the World of Science,” in Hebrew).

The boy’s father lifted him up to the opening, and he stuck out his head. “Not like that, Kalmankeh, feet first,” his father said. “Everyone in the car stared at me, encouraging me to jump,” Perk recalled. “Before I jumped we didn’t cry and we didn’t kiss each other. It was a terrible goodbye.” His father told him, in Yiddish, the words that he never forgot: “Kalmankeh, du zahlst zein a mensch” (Kalman, be a man), and pushed him out.

“That sentence remained with me my whole life. It didn’t matter whether I became a professor or a cobbler, the important thing was to be a good person. At 14, in shorts and a single shirt, I jumped from the train into a hostile world. In terrible distress, I left my loved ones to their fate, and in retrospect, I went on and I succeeded in preserving their memory,” Perk recalled later.

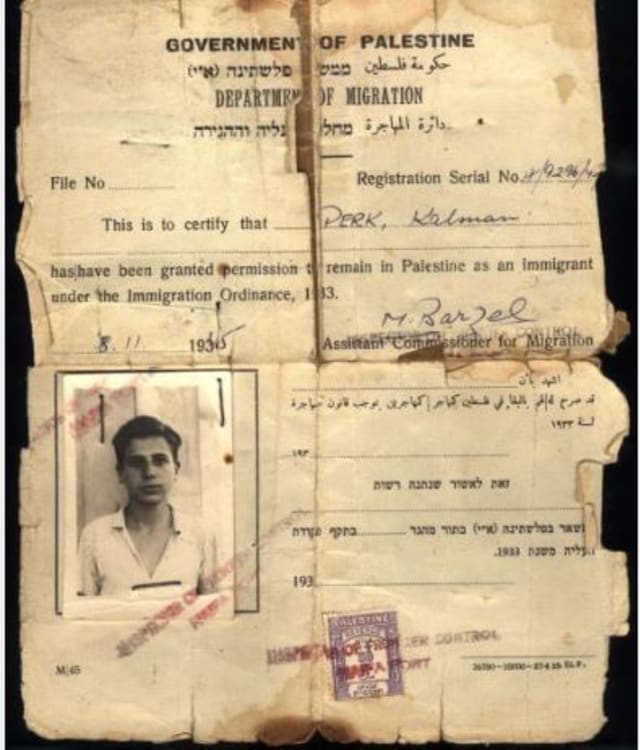

His mother, Dora (Finkelstein) Perk, was murdered in the Stutthof concentration camp; his father, Shimon, in Dachau. After escaping from the train, Kalman began walking eastward, to the Russian front. He adopted a Lithuanian name and identity, and survived. In October 1944 he wrote a letter to an uncle in pre-state Palestine – Prof. Elimelech Perk, a veterinarian: “I am Kalman Perk, the son of Shimon Perk, am writing to tell you that at the age of 14 I remained alive, the only one out of our family in Lithuania. With a bleeding heart I write the terrible news about the most beloved and precious family. Help!!! The Germans exterminated 99 percent of Lithuania’s Jews and by chance I, Kalman Perk, remained alive.”

Thanks to an immigration certificate arranged by his uncle, Kalman came to Palestine in 1945. He graduated from the Hebrew Gymnasium high school in Jerusalem, and went on to serve in the Lehi pre-state underground militia and to fight, in Jerusalem, in Israel’s War of Independence. He took part in the occupation of Deir Yassin and was shot and wounded by a sniper from the roof of the Notre Dame monastery in Jerusalem. He later served as a culture officer in the Israel Defense Forces.

In the 1950s, Perk studied veterinary medicine in Bern, Switzerland. His career choice was motivated in part by trauma that he carried with him from his time in the Kovno ghetto, from what he called the “pet aktion.” One day the Germans told the Jews that raising pets was prohibited, and ordered them to bring all their pets to the courtyard of an abandoned yeshiva. “ were brutally slaughtered, down to the very last one. Afterward they were not buried, and they remained strewn about the yard,” Perk recalled. A few days later, Perk joined a group of teens in organizing a burial. On another occasion, Perk said, he rescued a pregnant doe rabbit and brought it to the attic of his house, where she gave birth to a litter. When the Germans began to burn down the ghetto, he set them free.

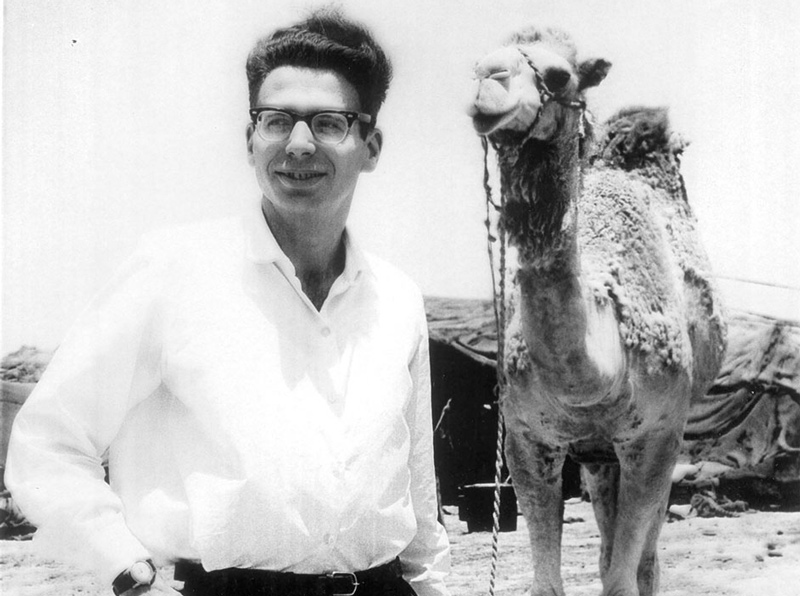

Perk founded and headed the department of anatomy and physiology and the Koret School of Veterinary Medicine at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. He specialized in veterinary oncology and virology and studied, among other things, a virus that causes lung cancer in sheep and viruses that cause leukemia in mice.

Two of Perk’s children, who were named for his parents, died young. Dorit, who was named for her grandmother Dora, was a young girl when she died of cancer. Shimon, a veterinarian specializing in poultry, died suddenly at age 60. Kalman’s wife, Ruth Yahalom, died in 2011. Prof. Kalman Perk died in June, at the age of 89. He is survived by his son Jonathan Perk, a physician living in New York, and by his grandchildren.