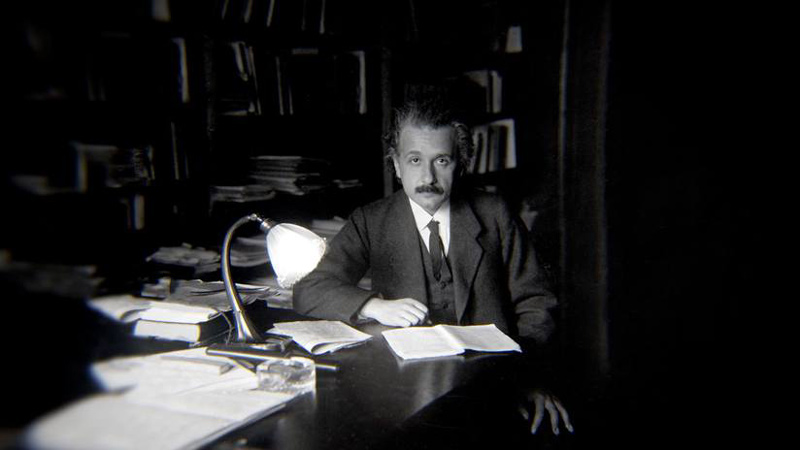

When Albert Einstein looked up into the night sky a century ago, the known universe consisted of only a single galaxy. And in that world, in the early part of 1919, very few people outside of Germany had heard of Einstein. Even Einstein himself was doubting his worth. He had just signed his divorce papers. He was dealing with health issues. His theory of relativity had yet to be proven. But then came May 29, 1919. That’s the day when Einstein became immortal.

During a solar eclipse in 1919, exactly 100 years ago, his theory became the backbone for modern-day astrophysics. But that was just the beginning: Part of Einstein’s conclusion was the existence of something called “dark matter,” a mysterious and invisible particle that nobody had observed just yet.

A new film called “Chasing Einstein,” which debuts this weekend, tracks the various scientists around the globe who have dedicated their lives to search for this dark matter – while others are working on an entirely new theory of gravity. The film is bookended by the works being done at the particle accelerator at CERN in Switzerland as well as at the LIGO gravitational wave detector here in the United States – two of the largest science experiments ever attempted.

The new film was directed by Steve Brown and Timothy Wheeler, and written by Eric Myerson. “What we hope this film does is lay out the current day tension around Einstein’s vision of the universe and why this matters,” said Wheeler. “This tension could lead us to the next scientific revolution, in the same way that Einstein brought us into a new era of understanding 100 years ago.”

Added Brown: “Our abilities to measure and predict are incredibly advanced today, but the big questions are as mysterious now as they have ever been. We all seem to have the same big questions and you don’t need a PhD in physics to be curious about them.”

The film is being released amid a resurgence of movies and television shows featuring the world’s favorite genius. Einstein has appeared in everything from a time-traveling superhero TV show to a 10-part miniseries about his life for National Geographic. That series was produced by Oscar-winning filmmaker Ron Howard. “What was the most enticing was diving into aspects of the Einstein you didn’t know,” Howard explained. “As a young man, he was free-thinking, a Bohemian. He loved women, loved nature. He was determined to understand and that just kept driving him. The epitome of curiosity just kept fueling him.”

Just this month, the CBS network announced that they will be making a new detective series called “Einstein.” The show follows the fictional great-grandson of Albert Einstein who is pressed into service helping the local police solve their most puzzling cases.

Hanoch Gutfreund is the director of the Albert Einstein archives at Hebrew University in Israel, a school the physicist helped establish. “The interest in Einstein does not fade into history. If anything, if one can say anything about this, the interest in Einstein increases with time. It’s greater now.”

As for the “Chasing Einstein” documentary, co-director Brown believes it is more relevant in the current moment than ever before. “The open questions in physics today are so big that it feels like we are bound for another major shift in our thinking,” Brown said. “The only thing we know for sure is that everything we think we know today might turn out to be wrong, and a future generation will wonder how we possibly believed what we believe today. That’s what makes this an exciting time in physics.”