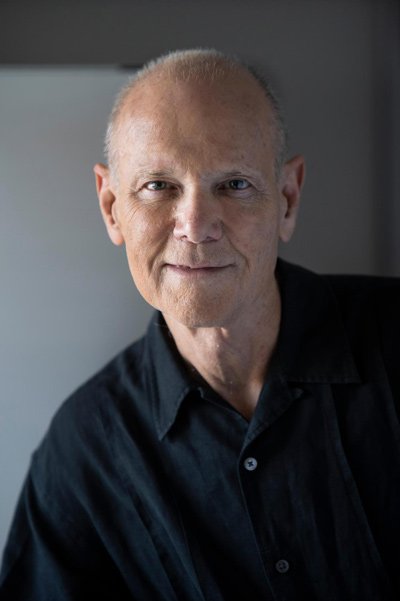

Editor’s note: Lead researcher in this study, Prof. Yinon Ben-Neriah, recently won the EMET Prize for his work with cancer, and in April received a prestigious European Research Council Advanced Grant for his research into the treatment of adult leukemia.

Israeli researchers have found that antioxidant-rich foods, including black tea, chocolate and berries could increase risk for certain colorectal cancers.

The scientists from Hebrew University in Jerusalem turned up the finding while investigating a longstanding medical question — why cancer of the colon is a leading cause of cancer death, but the illness rarely takes root in the neighboring small intestine, which is much larger.

The research team led by Professor Yinon Ben-Neriah found that cancer mutations in certain areas of the body, including the gut, can actually help the body fight cancer, but that high levels of metabolites, like those found in antioxidant-rich foods, promote the growth of bowel cancers.

Around two percent of gastrointestinal cancers happen in the small intestine, and 98% in the colon, which contains much higher levels of gut bacteria.

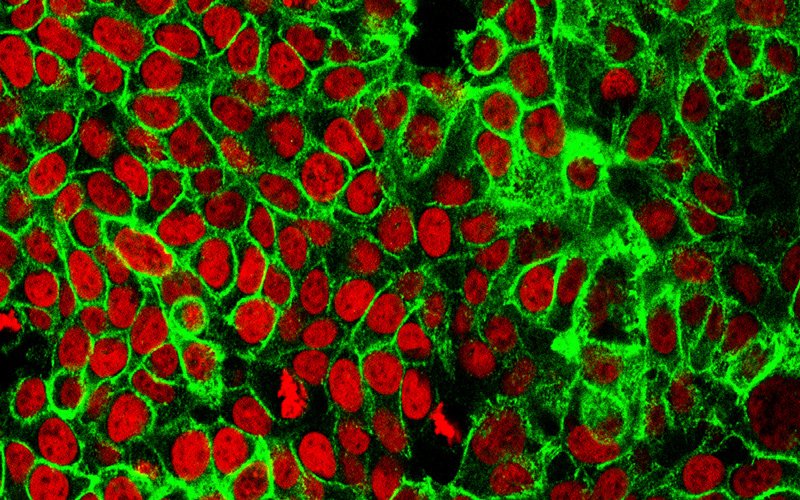

The researchers focused on a gene called TP53, which is found in every cell, and produces a protein called p53. The protein suppresses genetic mutations, which can lead to cancer, but when p53 gets damaged, it can abet the growth of tumors.

The researchers introduced mutated p53 proteins into mice. The small intestines converted the mutated proteins back to normal p53 proteins, which became “super-suppressors,” more effective at suppressing cancer growth than other p53 proteins.

The colon, however, did not convert the mutated p53 proteins, which continued to promote the spread of cancer.

“We were riveted by what we saw,” Ben-Neriah said in a statement Wednesday. “The gut bacteria had a Jekyll and Hyde effect on the mutated p53 proteins. In the small bowel they totally switched course and attacked the cancerous cells, whereas in the colon they promoted the cancerous growth.”

The researchers then used antibiotics to kill off other organisms in the colon to test whether gut flora played a major role in the process. After killing the bacteria, the p53 in the colon did not accelerate cancer growth.

An analysis showed that the bacteria were producing metabolites, or antioxidants, which were helping the cancer grow.

When the scientists gave the mice a diet rich in antioxidants, the mice’s gut flora spurred on p53’s cancer promotion.

“Scientifically speaking, this is new territory. We were astonished to see the extent to which microbiomes affect cancer mutations — in some cases, entirely changing their nature,” said Ben-Neriah.

The researchers said that people at risk for colorectal cancer could screen their gut flora and monitor their diet for antioxidant-rich foods.

The findings were published on Wednesday in the science journal Nature.