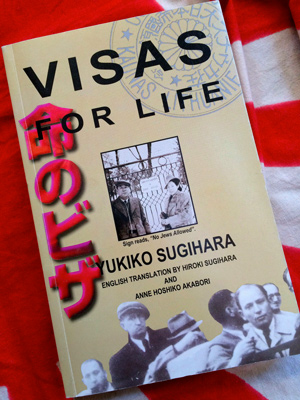

Editor’s note: Nobuki Sugihara’s father, Chiune, a diplomat at the Japanese consulate in Kaunas, Lithuania during WWII, saved thousands of Jews by issuing transit visas in defiance of government regulations. Later, in 1968, when the Israeli government asked how Israeli survivors could help him, he had only one request: a scholarship for his son Nobuki to attend Hebrew University.

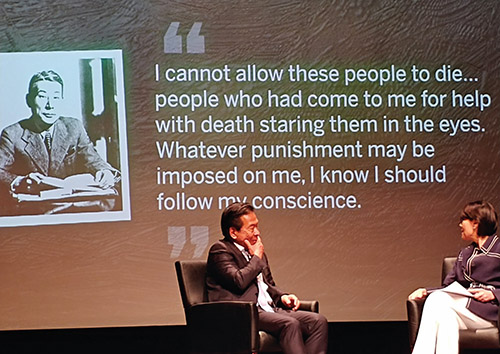

Nobuki Sugihara, son of Chiune, a righteous among the nations, met with Holocaust survivors and their descendants at a pre-event reception. Later we all listened to a conversation that Nobuki had, in English, with award winning journalist Anne Curry.

In 1940 Chiune was a Japanese diplomat at the consulate in Kaunas, Lithuania (Kovno). He defied his government’s orders regarding issuing visas. Unable to write destination visas for the people desperate to flee Nazi persecution, Chiune decided to issue transit visas, despite government requirements.

In 1940 my father fled Poland as part of a group of students from Yeshiva Tomchei Temimim Lubavitch. The students made their way from Vilna across Russia via the Trans-Siberian railroad to Vladivostok, where they boarded a boat bound for Japan. They spent months in Kobe, Japan, and were eventually resettled by the Japanese in a ghetto in Shanghai, China. There my father spent the rest of World War II. Movement was restricted, but the yeshiva operated. Food was often scarce, but my father survived. One of his brothers was buried in Shanghai, a victim of typhus. My father lost most of his sight as a result of malnutrition. He, an older brother and an older sister survived and eventually built their lives in the United States.

The Chanowitz family: children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren – more than 100 of us – all owe our lives to the courage and conviction of Chiune Sugihara.

Nobuki Sugihara is intent on preserving his father’s legacy. During his conversation with Curry, he mentioned that although he was glad that films were being made about his father, the films used hyperbole and “Hollywoodization” to market his father’s story. Nobuki explained that the actual facts, simply presented, “are drama enough.”

That night I learned new things about Chiune Sugihara’s heroism. I already knew that he had agonized for days as he sent telegrams to the Japanese home office in Tokyo, asking for permission to issue transit visas to the people begging for his help. I knew that the Soviet authorities were closing down all foreign consulates in Kaunas (Kovno) in July, 1940. That night I learned that Chiune negotiated with the Soviets to allow him to stay an extra month, through the end of August; that was the time he estimated he would need to issue thousands of visas to those waiting in line at all the consulates.

I knew that in the years after Chiune and family returned to Japan he could no longer work in the Foreign Service. He tried his hand at various pursuits in an effort to feed his family. That night I learned that although he knew he had written 2,148 visas, Chiune never knew how many of those estimated 6, 000 people survived the lengthy journey, found safe haven and survived the war.

Nobuki described how in 1968 the Israeli embassy in Tokyo contacted his father with the news that one of his visa holders was in Tokyo and wanted to meet and thank him in person. Nobuki accompanied his father on the trip. For the first time Chiune learned of Holocaust survivors living in Israel who owed their lives to him.

When Chiune was asked how the Israeli survivors could help him, the father motioned to his son and said: “I would like it if he could get a scholarship to attend Hebrew University in Jerusalem.” And so, that night, I learned that Nobuki is a graduate of Hebrew University. During a question and answer period I learned that Nobuki stayed in Israel and worked in the diamond business in Tel Aviv until moving to Antwerp. Nobuki answered the question about what he did after Hebrew University in fluent Hebrew – and the audience roared with delighted laughter and clapped enthusiastically.

During the question and answer session, as microphones were passed around in the audience, Sugihara Jews spoke, expressing their thanks to Chiune for risking everything to do the right thing. I sat there with my two sons (my daughter was too far away to join in person and used the video link). When I had the microphone in hand, I shared my thanks to Sugihara and his family for their sacrifice, and exhorted those assembled to continue to share the Sugihara story. I felt my father’s approval from the great beyond, and the weight of future generations at my back.

Nobuki was asked if he could explain what motivated his father to defy direct orders and issue visas to people running for their lives. Nobuki responded: “My father was stubborn. He didn’t always follow others’ ideas. My father followed his ideas. This time he was right!”

The evening ended with a standing ovation. Then there were more conversations, hugs and phone numbers exchanged. Among those people I met at this “family” reunion were people I had not seen in years: someone from my high school graduating class, a former camp mate, former business associates, former employees. We are all Sugihara Jews – real family! Who knew?

For more information, visit Sugiharavisas.org.