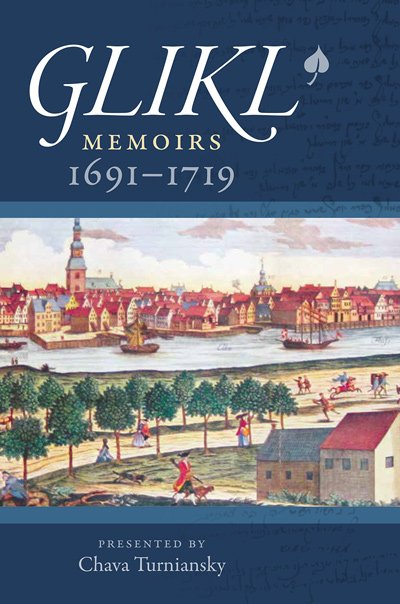

Last October my wife and I and about 60 other mostly Jerusalem residents attended a series of 7 weekly lectures at the Zalman Shazar Center in Arnona. For one and a half hours each week we were transported to other realms and incarnations of Jewish life in Europe. This was our third series of Yiddish lectures delivered by Prof. Emerita Chava Turniansky of the Hebrew University, who is one of the most knowledgeable Yiddish academics in the world. Her fields of research include the history of Yiddish literature and Ashkenazi culture, especially in the Early Modern Period. She is a member of the Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities, and is an Israel Prize Laureate. Her critical edition and Hebrew translation of Glikl’s Memoirs (Glückel of Hameln) was awarded the Bialik Prize in Jewish Studies.

Chava was born and raised in Mexico in a Yiddish-speaking home.

“My parents refused to answer me if I spoke in Spanish,” she once told an interviewer. “For many Jewish families who emigrated from Eastern Europe to Mexico, speaking Yiddish was their way of maintaining European Jewish culture and identity.”

She made aliyah in 1957 and failed to find work as an elementary school teacher. She consequently went back to university and enrolled in Yiddish studies, and went on to acquire a PhD in Yiddish Literature. Her latest literary efforts include revisiting the world of Glückel of Hameln in a book just published by Brandeis University titled, The Warning Song and the Medlars: Two Stories.

Glikl Bas Yehuda Leyb was a Jewish businesswoman and diarist. Written in Yiddish over the course of 30 years, her memoirs were originally written for her descendants to remind them of their Jewish heritage. Glückel’s diaries are the only known pre-modern Yiddish memoirs written by a woman.

When Turniansky arrived in Israel, she found herself in the midst of a struggle between Yiddishists and the academic authorities to gain acceptance for Yiddish to be taught as a language at the Hebrew University. At that time, the early Zionist founders of the state did everything to make Hebrew the lingua franca of the country by discouraging the use of any other language, especially Yiddish. Following several unsuccessful attempts, the Hebrew University finally opened its first Department of Yiddish in 1961.

“There were protests against the Hebrew University’s decision to open the Yiddish department,” Turniansky explained. “Yiddish was considered the language of galut (the Diaspora), and Hebrew was the pure form of verbal expression – there were posters throughout the university saying it was shameful to open such a department and that Yiddish was only jargon. People were shocked when I told them I was studying Yiddish in university. They asked, why would you do that?” She went on to remind us, “Today, the situation is very different. Yiddish is a language that is warmly embraced by scholars and students alike.”

Judging by the eagerness with which Chava’s students attend her Tuesday classes, her observations are quite correct. She explains that Yiddish has made a comeback not only among religious Israelis but also among secular ones. From my own observations I noticed that most of us attending the Tuesday lectures are in our retirement years, though a few youngsters help to bring down the average age range by about 30 years! So why do people attend her classes? In most cases, it is the desire to connect with our roots and our rich Jewish Ashkenazi heritage.

At the beginning of her first lecture, Prof. Turniansky reinforced the idea of how geography makes a huge impact on the evolution of language. Early on there was only one type of Yiddish spoken in Europe. It strongly resembled medieval German and was spoken in Western Europe for a few hundred years. The language was known as Ivri-Taitsch. Over time the dialect became heavily influenced by waves of Jewish migration often brought about by pogroms and persecution. Ever since the destruction of the first Temple, Jews were on the move and seeking refuge in foreign lands. At first the migrations were within reach of their ancestral homeland in the Middle East. They ended up in places like Babylon (Iraq), Egypt, Persia (Iran), Turkey and Spain. But gradually Jews moved further afield to Rome, Greece and Gaul and then to Ashkenaz, the ancient Jewish name for the lands that make up modern Germany.

It was there in the 9th century that Yiddish took root. The written language has always been penned in Hebrew script in a way that is very different from Modern Hebrew writing. The language further evolved from Western Yiddish (Maariv Yiddish) with its mainly Germanic influence into Eastern Yiddish (Mizrach Yiddish) in the 18th and 19th centuries when Jews began to migrate eastward to Poland, Lithuania, Latvia, and Russia. Here the language became transformed with many Slavic and “foreign” words entering the vocabulary. Wherever Jews settled, they established their own use of the language, adopting the buzzwords and jargon of the cities and shtetls in which they resided. In the Postmodern era, Yiddish merged into a rich and distinctive language with its own literature contributed to by writers like Sholem Aleichem, Isaac Leib Peretz, Isaac Bashevis Singer and Shalom Asch, to name but a few.

For me the experience has been a journey into a world of déjà vu, at once familiar and yet completely new. Originally from South Africa, I grew up in a house where Yiddish was spoken between my parents and grandparents. Because we had to learn Afrikaans, a Germanic sounding dialect of Dutch, Yiddish was less difficult to fathom. Ninety percent of South African Jewry hailed from Lithuania and spoke Litvishe Yiddish. This Yiddish (spoken in Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, Belarus and parts of Russia) was always considered the most pure form of Yiddish, given that it was the closest to German. Fortunately for me, Prof. Turniansky speaks in a clearly articulated and pronounced Litvishe Yiddish. During her classes I often sit mesmerized and transported back to my childhood, as if I were eavesdropping on my grandparents. My Yiddish was never fluent; however, my life’s journey took me to Switzerland where I learned German. Later, I married my American wife whose parents were Polish Holocaust survivors. Like many Jews in Eastern Europe, they lived in a country where the borders kept changing and they ended up speaking Litvishe Yiddish as opposed to Galitzianer or Polish Yiddish, which initially was more difficult for me to understand.

One fascinating session of lectures in the series encompassed reading letters written in Vaybertaitsch (women’s Yiddish). This included a letter from a 17th century Yiddish-speaking widow living in Cairo addressed to her Ashkenazi family back in Poland. Amazingly, the letter was sent from Cairo where she had married a Sephardi man. The letter is a heartbreaking account of the woman’s plight, where she describes her poverty-stricken circumstances and appeals for financial help from her relatives. The letter was found in the Cairo genizah. In another heartbreaking dispatch that we studied together from the same period, we were made aware of the age old phenomenon of spousal abuse. In this letter, a young married orphaned woman living in Poland writes to her wealthy uncle in Germany appealing for his help. She describes how her husband favors his mother and his sisters, and how he neglects her and treats her like a servant, humiliating her in front of his family and their children. Pitifully, the woman explains that she is hungry and that her spiteful husband deprives her of everything. The reading of this letter was a chilling reminder of how disenfranchised, helpless and vulnerable women were throughout the ages.

One fascinating session of lectures in the series encompassed reading letters written in Vaybertaitsch (women’s Yiddish). This included a letter from a 17th century Yiddish-speaking widow living in Cairo addressed to her Ashkenazi family back in Poland. Amazingly, the letter was sent from Cairo where she had married a Sephardi man. The letter is a heartbreaking account of the woman’s plight, where she describes her poverty-stricken circumstances and appeals for financial help from her relatives. The letter was found in the Cairo genizah. In another heartbreaking dispatch that we studied together from the same period, we were made aware of the age old phenomenon of spousal abuse. In this letter, a young married orphaned woman living in Poland writes to her wealthy uncle in Germany appealing for his help. She describes how her husband favors his mother and his sisters, and how he neglects her and treats her like a servant, humiliating her in front of his family and their children. Pitifully, the woman explains that she is hungry and that her spiteful husband deprives her of everything. The reading of this letter was a chilling reminder of how disenfranchised, helpless and vulnerable women were throughout the ages.

Chava’s lectures were not all gloom and doom. In fact, one of the very first sessions that we attended was filled with riotous laughter after we were introduced to a compendium of Yiddish expressions followed closely by an assortment of Yiddish curses! An hour and a half later we staggered out of the auditorium still laughing and clutching our aching sides. With her deep, smoky voice and inimitable delivery, Chava began by telling the old joke about three people, a Christian, a Moslem and a Jew. They were discussing their weapons. The Christian mentioned that his most lethal weapon was a gun. The Moslem said that his most dangerous weapon was a sword, at which point the Jew piped up and said, “The Jew’s most deadly weapon is his tongue!”

She went on to demonstrate with a number of examples of devastating Yiddish curses:

A groys gesheft zol er hobn mit schoyre: vus er hot, zol men bay im nit fregn, un vos men fregt zol er nisht hobn.

“He should have a large store with merchandise: whatever people ask for he shouldn’t have, and what he does have shouldn’t be requested.”

The above was milder than many of the others, some of which are unrepeatable.

One of the funnier ones had us rolling in the aisles:

Es zol dir dunern in boykh, vestu meynen az s’iz a Homon klaper.

“Your stomach will rumble so badly, you’ll think it is a Purim noisemaker.”

Apart from the nostalgic aspects of learning and listening to Yiddish, there is also the intriguing intellectual element of the language, which is deeply rooted in our Jewish heritage, religion and culture, often infused with Tanachic and Talmudic influences. Even some of the curses are nuanced with biblical references:

Er zol hobn paroys makes bashotn mit oybes kretz.

“He should have Pharaoh’s plagues sprinkled with Job’s scabies.”

For an 83-year-old, Chava’s stamina is extraordinary. She stands in front of the large crowd holding a microphone for a full hour and a half, managing to engage every single member of the audience with her sharp wit, wry humor and crystal clear delivery. Her knowledge of her subject, ancient references and all things Jewish, including her impeccable command of Hebrew, is awe-inspiring.

One of the sadder aspects of attending Prof. Turniansky’s lectures is knowing that they will eventually come to an end. At one point she made us aware of the fact that the spoken Yiddish of Der Alter Heim (the Old Country) will soon disappear as the older generation of Yiddish speakers begins to die out.

She referred to the fact that even though a form of Yiddish is spoken in the Haredi Hasidic community, it is not the same as the Yiddish that she teaches. Chava is one of Israel’s national treasures, and judging by the incredible response of her audience each week, it is my sincere wish that the cultural guardians of our Jewish heritage in Israel and the Diaspora will continue to share, teach and disseminate some of Prof. Turniansky’s precious jewels that make up her life’s work, much of which can be read and seen on social media and the Internet.